One thing that has helped me personally is understanding that Russian is a very systematic, almost mathematical language with its own internal logic.

The cases are there to help you understand how each word functions in a sentence. The imperfective/perfective verbs are there to help you understand the relation verbs have with their consequent actions within a specific time frame. The verbs of motion are there to help you come to grips with how you navigate across space.

Which is why I am often unimpressed by many people complaining about how Russian is a horrific language with horrific grammar and whatnot. I think Russian can be a very easy language as long as you understand that the grammar is there to help, not hinder.

Remember, the grammar is there to help, not hinder.

The rest is just rote memorisation.

Now, if you want a logical language that holds your hand every step of the way, take Russian.

I will guide you through a basic understanding of how cases function.

Remember, this is a basic outline of how grammar works — there is far more than you need to learn. But hopefully with this answer you will gain a better understanding of how Russian grammar functions.

I am also going to assume that you already know the Cyrillic alphabet, conjugations, genders, plurals and their basic exceptions, simply because I don’t really have the time to go through them, and also because if you’re learning Russian and still don’t know that information, you should really be looking into that before embarking on the meatier parts of Russian grammar.

CASES.

What are they?

Cases are grammatical markers that denote the function of nouns, pronouns, adjectives, cardinal numbers and participles in any given sentence. There are six main cases in Russian — nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental and locative/prepositional.

There are also remnants of the partitive case and the vocative case, but they are really only remnants and I see no reason to go through them here.

How do they work?

Now, the one thing that Russian children are taught in school — and this is something you should adopt as well — is to think of cases as attempts to answer questions. I’ll modify this a bit to make it a bit easier for learners.

Nominative (nom.): is this word the subject of the sentence?

- Кто подарил книгу? Мария подарила книгу.

- Who gave the book? Maria gave the book.

- Ты - мой друг.

- You are my friend.

Accusative (acc.): is this word being directly affected by the subject? [If paired with a preposition] Where is the subject going/to what direction is the subject headed? who/what/(to) where?

- Кто подарил книгу? Мария подарила книгу.

- Who gave (what?) the book? Maria gave (what?) the book.

- Я вчера увидел на рынке тебя и Роберта.

- I yesterday saw in the market (who?) you and (who?) Robert.

- Я сел в автобус.

- I sat (to where?) (to) the bus. / I got myself seated on the bus.

Genitive (gen.): of what? of whom?

- Пятьдесят оттенков серого

- Fifty (of what?) shades (of what?) of Grey

- Note here that ‘shades’ is being affected by ‘fifty’ and ‘Grey’ is being affected by ‘shades’. This will become important later.

- Здесь много людей.

- Here a lot (of whom) of people/there are a lot of people here.

- Это книга Роберта.

- This is the book (of whom?) of Robert ie. This is Robert’s book.

- Нет Роберта. Нет книги.

- There is no (of whom?) Robert ie. Robert isn’t (here)/there is no Robert. There is no (of what?) book ie. There is no book.

- The genitive case also follows negation, which is often seen as a grammatical quirk. I like to think of the negation “нет” as being transformed to the subject of the sentence, which would make it easier to come to grips with the fact that the genitive case affects “нет”. If this is still confusing, just learn this grammar rule.

- Note: the genitive case follows ‘для’ meaning ‘for’ and ‘из’ meaning ‘from’, as well as prepositions the generally mean something along the lines of ‘by’, ‘through’ eg. у, сквозь, мимо, with the exception of через which takes the accusative case.

- The genitive case is also used in comparisons. “Я выше Роберта” → “I am taller than Robert”.

Dative (dat.): is this word being indirectly affected by the subject? to whom?

- Кто подарил тебе книгу? Мария подарила мне книгу.

- Who gave (to whom?) you a book? Maria gave (to whom) me a book.

- Скажи мне, что ты меня любишь.

- Tell (to whom?) me that you love me.

- Verbs such as ‘to say’, ‘to tell’ etc. often follow the dative case.

- Роберту нравится.

- (to whom?) To Robert, it is pleasing (Robert likes it).

Instrumental (inst.): how?

- Я пишу карандашом.

- I write (how?) (with a) pencil.

- Я увидел Марию расстроенной.

- I saw Maria (how?) upset. (Maria was upset)

- Эта книга была написана Робертом.

- This book was written (how?) (by) Robert.

- Другими словами, всё плохо.

- (How?) In other words, everything is bad.

- Note: the instrumental case often follows the preposition ‘with’ → с девушкой = with (a) girl.

Locative/prepositional (prep.): where? (alternatively) about what?

- Я сидел в автобусе.

- I was sitting (where?) on the bus. / I was seated on the bus.

- Мария в банке. Я на рынке.

- Maria is (where?) in the bank. I am (where?) at the market.

- Вижу в тебе много минусов.

- I see (where?) in you a lot of negative aspects.

- Мы говорили о тебе и твоей работе.

- We were talking about (about what?) you and your work.

How do they work in a sentence?

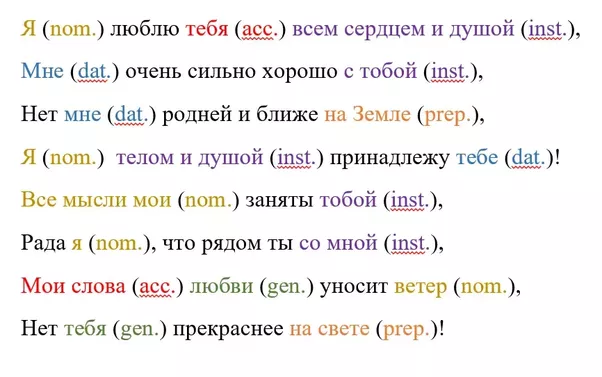

Now that we’ve got this far, let us see how different cases interact with one another, using (gasp!) real Russian. This is a random poem I found .[1] The first part of the poem goes like this:

Я люблю тебя всем сердцем и душой,

Мне очень сильно хорошо с тобой,

Нет мне родней и ближе на Земле,

Я телом и душой принадлежу тебе!

Все мысли мои заняты тобой,

Рада я, что рядом ты со мной,

Мои слова любви уносит ветер,

Нет тебя прекраснее на свете!

It is horribly cringey but it will do the trick.

If we break down all these parts into their component cases, this is what we get:

Grammatical analysis:

I (subject) love (who?) you (how?) all heart and soul,

(To whom?) To me very very good (how?) with you,

There is no (to whom?) to me dearer and closer (where?) on Earth,

I (subject) (how?) body and soul belong (to whom?) to you,

All thoughts my (subject) are busy (how?) you,

Happy I (subject) that close you (how?) with me,

(What?) my words (of what?) love are take away the wind (subject),

There is no (of what) (than) you more perfect (where?) in the world.

Translation:

I love you with all my heart and soul,

I feel extremely good being with you

There is nothing (no one) dearer and closer to me on Earth,

I belong to you, body and soul,

All my thoughts are preoccupied with you,

I am happy that you are close to me,

The wind takes away my words of love,

There is nothing (no one) more perfect than you in the world.

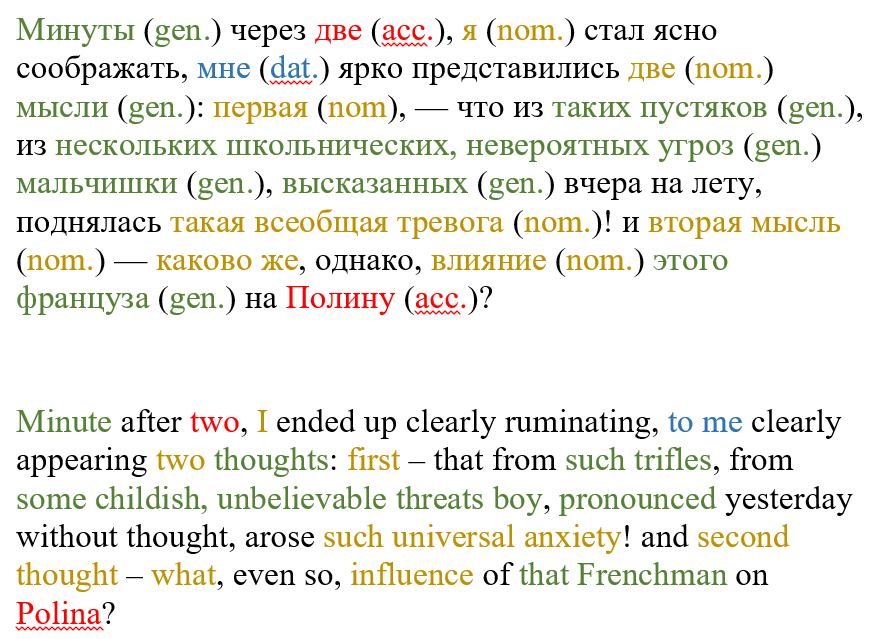

Okay, let’s take it up a notch. This is a sentence from the book I’m currently reading. Some of you will recognise it as The Gambler by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Минуты через две, я стал ясно соображать, мне ярко представились две мысли: первая, — что из таких пустяков, из нескольких школьнических, невероятных угроз мальчишки, высказанных вчера на лету, поднялась такая всеобщая тревога! и вторая мысль — каково же, однако, влияние этого француза на Полину?

Again, we shall break down the sentence into their corresponding cases, followed by a word-for-word translation into English that only just about makes sense (but will make more sense later, just you see!)

Now, let’s try to make sense of these cases.

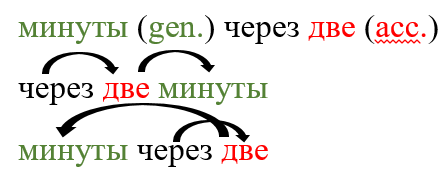

Минуты через две (after [about] two minutes): We have established above that через (‘after’) takes the accusative case, which should come as to surprise that ‘two’ thus takes the accusative case. But why then does ‘minutes’ take the genitive case?

It will make it easier if we break it down like so:

Hence you can see that it really goes like this: after (what?) two (of what?) minutes, where ‘after’ affects ‘two’ and ‘two’ affects ‘minutes’. In other words, ‘two’ almost functions as a noun that is capable of affecting other words around it.

Note: There are special rules for whether the genitive singular or genitive plural follows the cardinal numbers ‘one’, ‘two’, ‘three’, ‘four’, ‘five’, but that is beyond the scope of this answer, as we are only interested in seeing which cases work where.

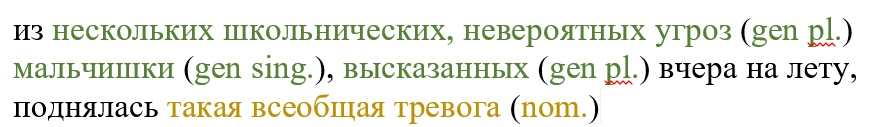

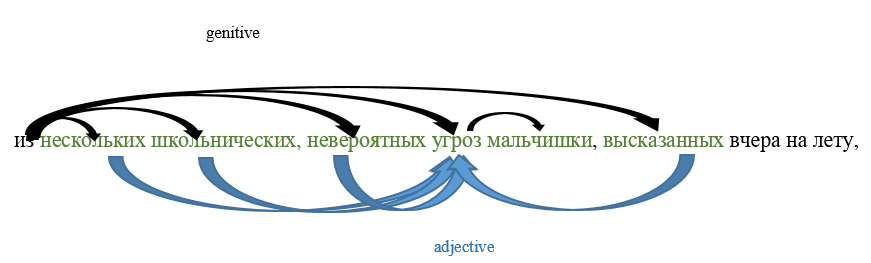

Moving to the middle of the paragraph with the long line of words in the genitive, you will see another example of how cases can help us understand how the language functions:

‘From such trifles’ is what this phrase is trying to say. We have also already established that ‘из’/’from’ takes the genitive. But why are both ‘such’ and ‘trifles’ here in the genitive, while in the phrase above через only affects ‘две’ and not ‘минуты’?

The easiest way to think about it is that here, ‘such’ is seen as an adjective affecting ‘trifles’, and hence the genitive case that follows ‘from’ must affect both ‘such’ and ‘trifles’ equally. In the other example above, the accusative function of ‘from’ is absorbed by ‘two’, which functions almost like a noun, and minutes is modified by ‘two’ in the genitive.

Now that we’ve got that cleared up, let’s move on.

This phrase is trying to say: From (of what?) some childish unbelievable threats (of whom?) of a boy, (of what?) pronounced yesterday in the spur of the moment, arose such universal anxiety (subject).

Wait, hang on, they’re all in the genitive case, right? But why is one word in the genitive singular and the rest in the plural? That doesn’t make sense, does it?

Oh, but wait, it does. You see, ‘some’, ‘childish’, unbelievable’ are all seen as adjectives that describe ‘threats’, which is in the plural. Hence, they all get modifiedby the preposition из into the genitive plural.

‘Boy’ (in the singular) in this case is a nouns that indicates the origin of ‘threats’ — it hence gets modified into the genitive singular by the noun ‘threats’.

What about ‘pronounced’ then? It is in the genitive plural — by deductive reasoning you can deduce that it is not meant to refer to ‘boy’ which is in the singular. It is hence supposed to refer to ‘threats’, which is in the plural. In this case, ‘pronounced’ gets treated as an additional adjective to the word ‘threats’ that gets modified into the genitive plural by the preposition ‘из’.

In other words, this is what it looks like:

The trick is to think of them all mathematically — 1 + 1 makes 2; adjective + noun get declined together, noun declines noun.

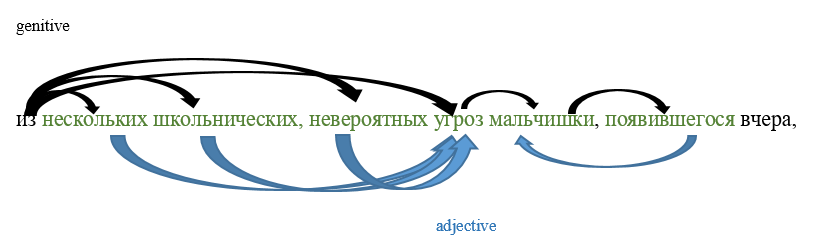

Let’s modify the last sentence a little bit (sorry, Dostoevsky!) to see how we can play around with Russian grammar:

Roughly translating to: ‘… from a few childish unbelievable threats of a boy, who appeared yesterday…’

What’s different here? Here, the difference is that the participle ‘who appeared’ is declined in the genitive singular, which indicates that it is meant to refer to ‘boy’ which is also declined in the genitive singular. As you can see, the participle no longer refers to ‘threats’.

See what I mean? When it comes to Russian grammar, the trick is to think logically, and deduce, deduce, deduce.

Woah, what is this? Within the span of one answer we have not only read half of a simple poem, but we’ve also read Dostoevsky, of all people. Where has time gone? :-)

If there is one thing to take away from this horrendously long answer, it is this: Russian grammar is there to help, not hinder.

Think things through logically, and with lots of practice it will become second nature.

And with time you will realise that Russian grammar can not only be understood, but it can be understood much more easily than you might think. Why? Because the language guides you every step of the way.

I hope this helps.

Footnotes

[1] Я люблю тебя всем сердцем и душой

Source: Quora.